Lumbar Disc Prolapse

How does it happen?

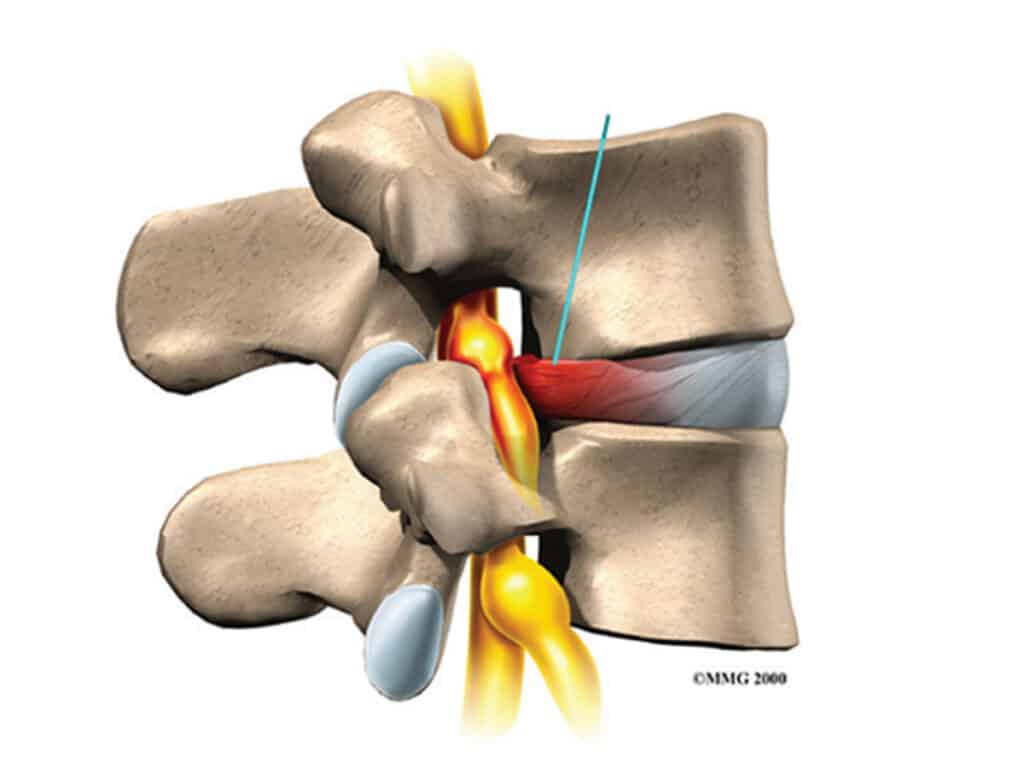

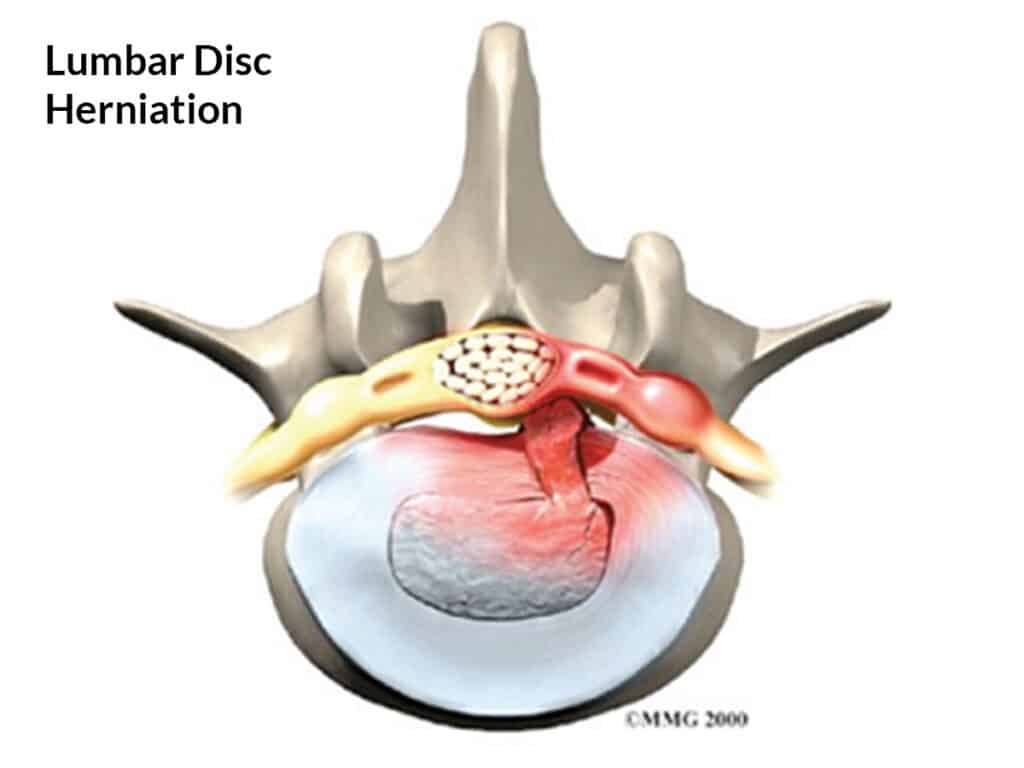

Unfortunately, our discs deteriorate with age. When we are children, the inner nucleus in our disc is like a soft gel and it is held in by the outer annulus which is tough and strong. With age, the nucleus dries out and becomes less spongy, and annulus becomes brittle and can split or crack. If the split extends through the annulus, the nucleus can squeeze out into the spinal canal and push on the nerves.

Why does it happen?

Disc aging or degeneration is a gradual process. A disc prolapse occurs when the annulus is too weak to prevent the nucleus prolapsing out. In many cases, no specific event causes the prolapse. It can be triggered by exertion or an injury, but a normal healthy disc cannot prolapse unless there is some pre-existing weakness or degeneration present.

What does it cause?

When the nucleus comes in contact with a nerve in the spinal canal, the nerve becomes irritated and inflamed and pain is felt along the path of the nerve. The nerve is inflamed by the irritant chemicals contained in the nucleus, as well as the pressure from the prolapse. The nerve can be damaged by the prolapse, causing muscle wasting, weakness, numbness, pins and needles and loss of reflexes in the leg. The damaged disc also causes back pain.

What happens to the prolapse?

With time, the body ‘mops up’ the irritant chemicals. This usually happens in the first six weeks, explaining why many people start feeling better. The prolapse eventually shrinks but this can take from a few weeks to many months. If the prolapse does not shrink sufficiently, pain can continue.

Can it be serious?

Occasionally, the disc prolapse is so large that it squashes all the nerves in the spinal canal, causing partial paralysis and loss of bowel and bladder control. This is called a cauda equina syndrome. It is rare but needs immediate surgery. More commonly, long term pressure on the nerve leads to chronic pain and possibly nerve damage. Sometimes a leg muscle stops working, causing weakness such as a foot drop, or part of the leg becomes permanently numb.

How is it diagnosed?

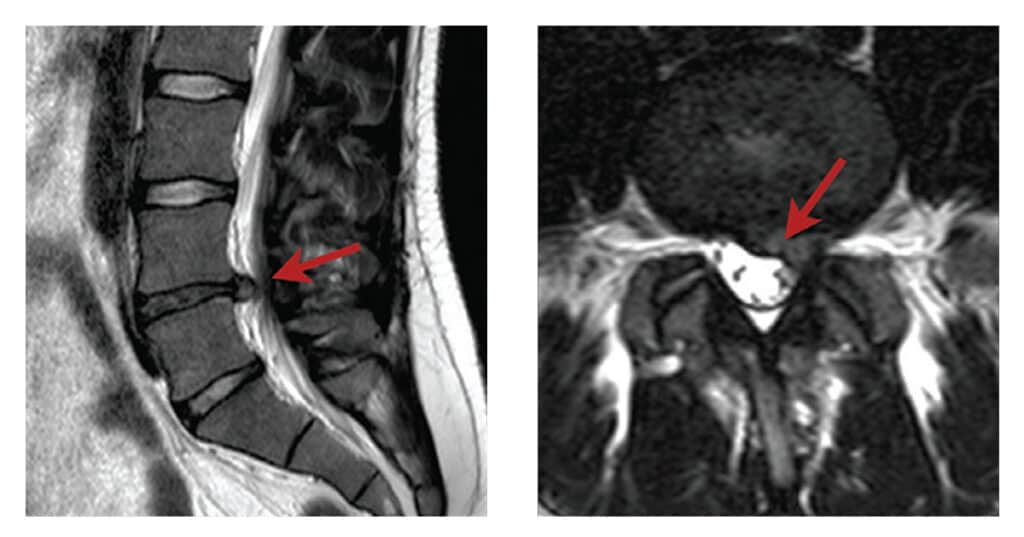

The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the symptoms and signs. It is suspected if there is severe leg pain and numbness or pins and needles along the known path of one of the lumbar nerves together with muscle weakness, loss of reflexes, numbness and pain on stretching the nerve. A scan is often used to confirm the diagnosis, especially if the pain is not settling and surgery is considered. An MRI scan is more accurate but sometimes a CT scan is ordered.

How is it treated?

Most disc prolapses get better by themselves in the first six weeks. During this time, the best approach is to avoid activities that flare up the pain (but strict bed rest is not necessary).

Tablets such as pain killers, anti-inflammatories and in some cases muscle relaxants can be used. Occasionally, an epidural injection of steroid or even steroid tablets can be used to settle the inflammation but the effects are temporary. A physiotherapist can offer advice about pain relieving techniques, ways to manage daily activities, and gentle exercise to maintain back mobility and fitness but hands-on treatment has a limited role to play.

If leg pain is severe and is not improving in the expected timeframe, surgery in the form of a discectomy is considered.

Lumbar discectomy

What is it?

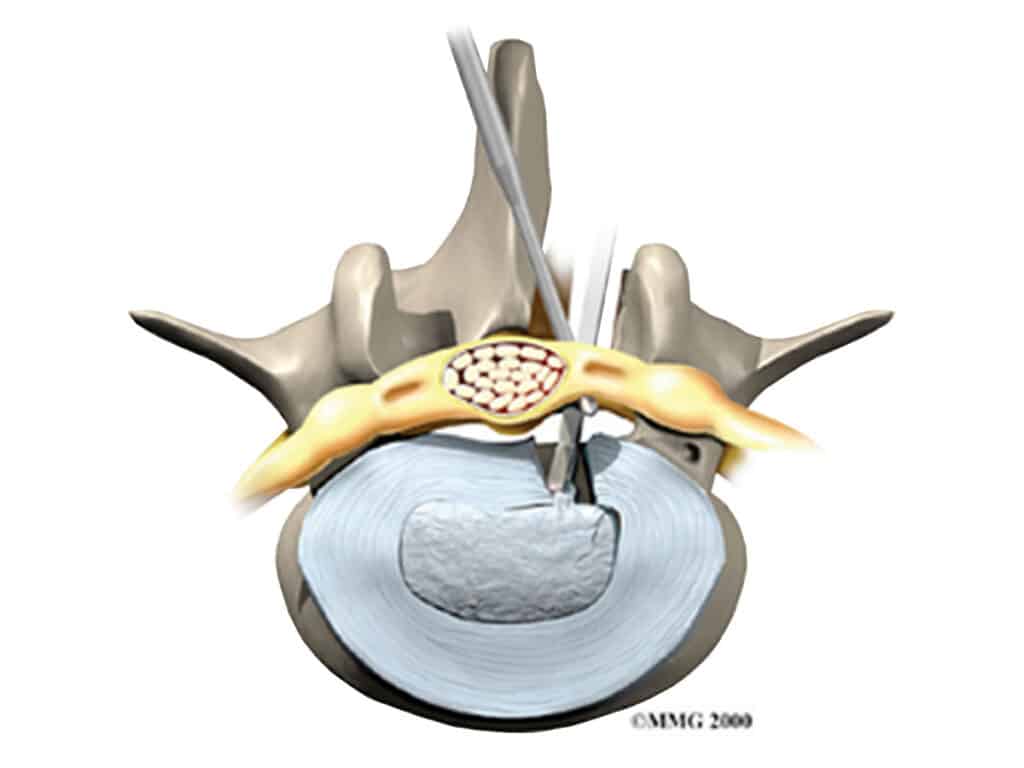

A discectomy is an operation to remove the piece of disc that has prolapsed into the spinal canal. It is a commonly performed, straightforward operation and is usually done as a day surgery procedure. The aim of the operation is to remove pressure from the compressed nerve and to relieve leg pain. It is successful in 90% or more of cases.

How is it done?

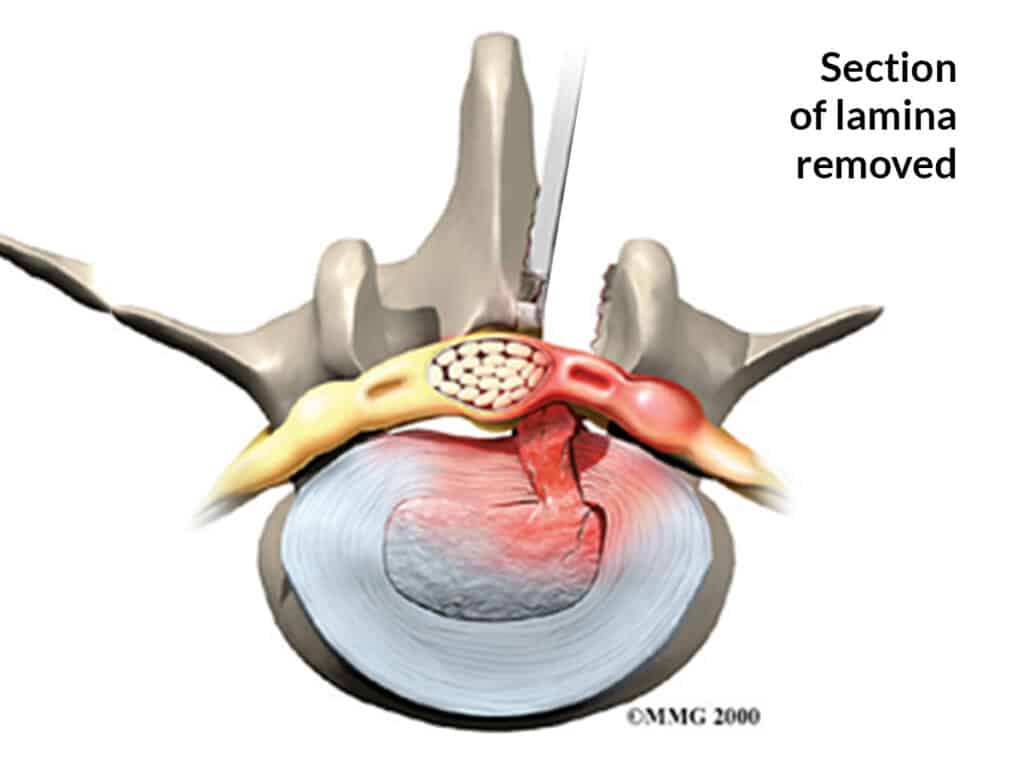

You are admitted to hospital on the day of the procedure. You are given a general anaesthetic and placed on the operating table face down with your hips and knees bent. The skin over your low back is cleaned. A needle is placed in your back and an x-ray is taken to make sure the correct level is operated on. A small (3 cm) incision is made in the midline of your low back and the muscles are separated from the bone and held apart with a specialised retractor. A small window is made between the vertebrae (in the posterior part called the lamina) to expose the dura (the spinal sac containing the nerves and the spinal fluid). A microscope is then used to improve vision and precision. The compressed nerve is found and moved aside to expose the disc. Sometimes a small cut has to be made in the outer part of the annulus to expose the prolapse, and sometimes the prolapse is already completely outside the disc. The prolapse is removed and the inside of the disc is checked for loose fragments, which are also removed. The whole disc is not removed – in fact most of the disc remains. Finally, some steroid and anaesthetic are placed on the nerve to settle pain and swelling, and the skin is closed with dissolving sutures. You wake up and go home when you are feeling fine and can walk safely.

What happens afterwards?

The main goal of your recovery is to restore and maintain spinal strength and flexibility and to avoid overloading the disc while the hole in the annulus heals. You will see a physiotherapist before you go home, who will give you advice and exercises. You will need to rest for two or three days, and then start increasing your activity level. After two weeks, you can drive and start going out normally. You can return to work after two to three weeks if your work is sedentary or after six to eight weeks if it is more physical. You need to avoid frequent bending and heavy lifting for six weeks, and you can return to sport after two to three months. You will see the physiotherapist at three weeks for some more exercises, and again at six weeks when you come back to see the doctor.

What could go wrong?

After surgery, you may have some ongoing leg pain, especially in the first few weeks. In most cases this settles nearly completely but if the nerve has been damaged by the prolapse, it may continue. Back pain may become a nuisance when you resume activity, and occasionally it can become troublesome if the disc damage from the prolapse does not settle down. If the hole in the disc does not heal, more disc may prolapse out in the future, and another discectomy operation may be required. Very rarely, a serious complication can occur during surgery or soon after, such as nerve damage or infection. Before deciding whether to have an operation, you need to discuss these risks with your surgeon.